Debra Stevens’ new baby arrives at Elephant Havens the same day I do. As trucks roll down a sandy road, Debra and her husband, Scott Jackson, walk ahead to the quarantine boma where half a dozen elephant handlers are making preparations. The boma, or livestock enclosure, is constructed with round eucalyptus poles sturdy enough to withstand the force of small elephants. The poles are spaced just far enough apart so that a handler can slide through sideways. This 16-by-16-foot covered corral was built about 130 yards from the larger structure that houses the sanctuary’s existing herd of nine elephant calves. The quarantine allows fresh rescues peaceful recuperation for weeks or months until they’re ready to join the others.

When Boago “Bee” Poloko steps out of one truck, Debra opens her mouth in a silent scream, and then she skitters across the sand toward him and jumps, throwing her arms around his neck and kicking her legs back. “A giiiirl!” she squeals.

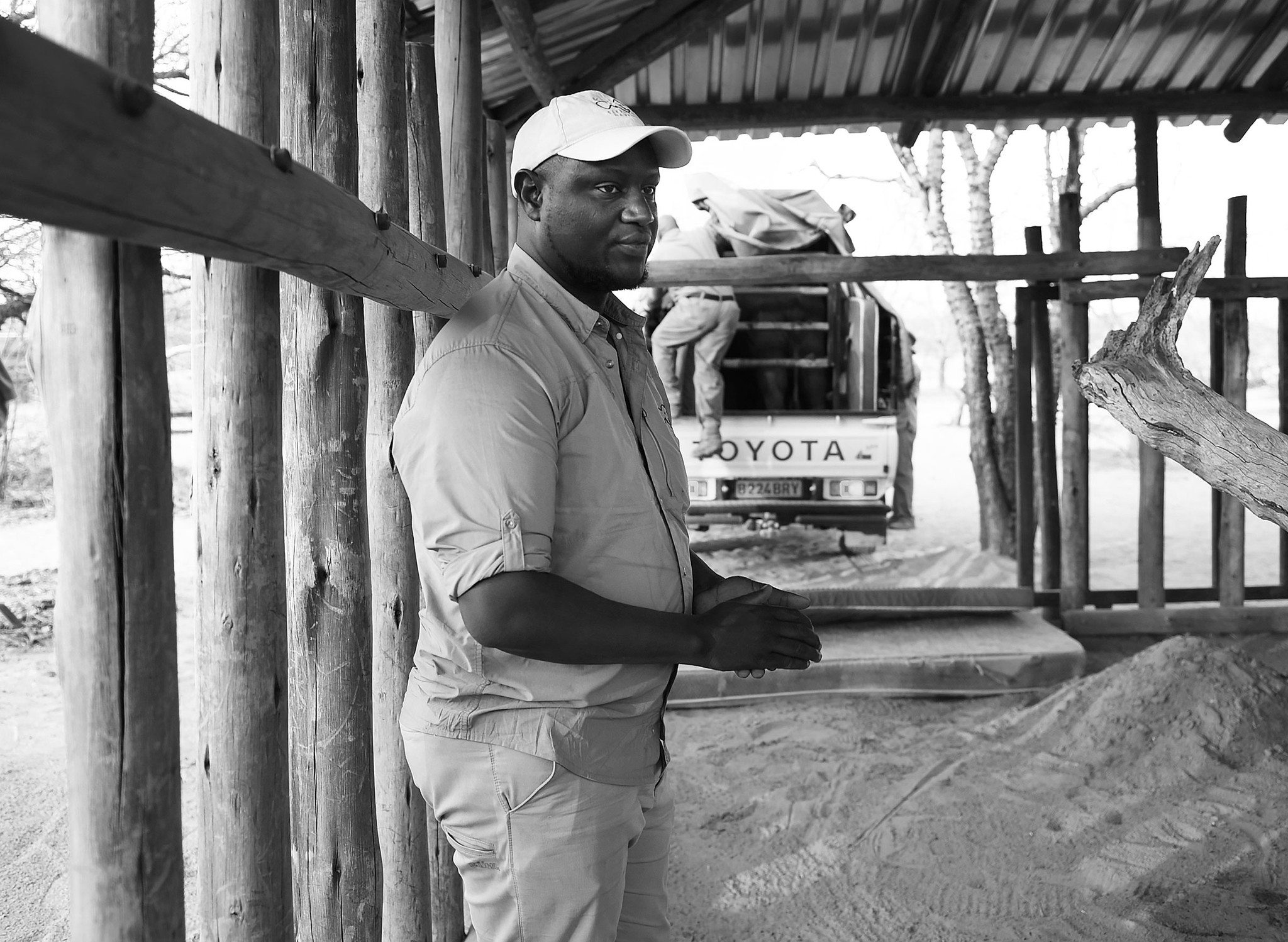

Bee wears khaki pants with a gray button-down, black boots, a white ballcap, and, in this moment, a huge grin. He is a large man with a head as round and shiny as a bowling ball. Maybe it’s his size, his direct manner of speaking, or the gold-rimmed Ray-Bans he usually wears, but 36-year-old Bee is unmistakably the boss of this operation. I get the sense that his smiles have to be earned, and a successful rescue is as worthy an occasion as any. This sanctuary, which Bee founded with Debra and Scott in 2018, is the first for orphaned elephants in Botswana, Africa, and the natural evolution of Bee’s family legacy. Both his dad and grandfather worked as elephant handlers.

Elephant Havens co-founder Boago “Bee” Poloko prepares the quarantine boma for a new rescue.

The mood turns sober when the young elephant stumbles out of the truck, into the boma. Her eyes were wrapped in cloth to help keep her calm on the journey, and she blindly bumps her head along the inside perimeter of the posts until Bee manages to reach through and loosen the blindfold. The elephant shakes her head, and the cloth falls. Once she sees humans, her ears flare out wide, contradicting her emaciated frame. A backbone juts up like a curved fin, and her hide hangs in loose folds where limbs meet midsection. After getting her bearings, she rushes in our direction, stopping short of the posts.

“OK, Debra, let’s move away,” says Onks Motamma, one of the lead elephant handlers, steering us back. The elephant rams her head into a metal gate and then jerks her trunk up and down as if to slap anyone who dares come near. “She’ll be screaming probably,” Debra says to me. “I’m going to warn you, because I know that’s going to be hard for me.”

That night, after dinner, Debra walks a dirt path to the main bomas to say good night to the rest of the herd. The nine calves have already guzzled their nighttime bottles, and their only sounds are low, sleepy grumbles. “They talk to each other,” Debra whispers. Elephants are believed to make infrasonic sounds that are too low for the human ear but can be felt by other pachyderms miles away via their sensitive feet. We never heard the new arrival scream, and Debra says she thinks the herd sent calming communications.

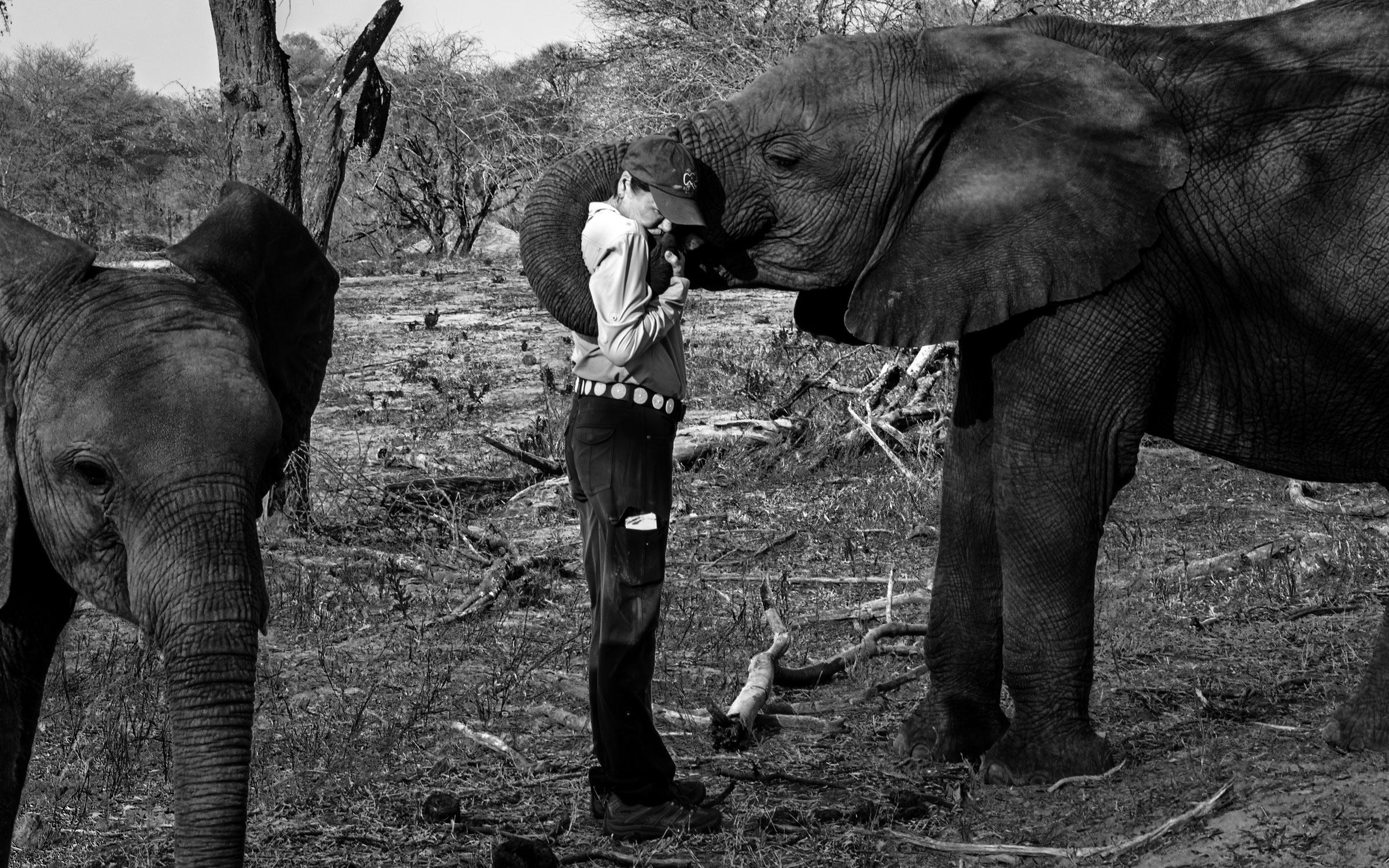

Debra approaches the first boma, and a large calf pushes his trunk through the posts. The 1-year-old calves are as tall as Debra’s waist, but 4-year-old Mofalodi towers more than a foot above her. Debra helps guide the elephant’s large trunk up over her left shoulder, around her back, to the right side of her waist.

A few of these babies were orphaned by poachers, and some got stuck in mud and were left behind. More often, though, a calf is orphaned when its mom is shot by a farmer. An elephant herd can wipe out a family’s entire crop in a matter of hours. As for Mofalodi, the handlers believe his mother died in an unusual incident when water holes contaminated with toxic bacteria wiped out 330 elephants. Mofalodi means “survivor.”

Once the calf has his trunk wrapped firmly around Debra’s body, he opens his jaws, showing a large, pink tongue. Debra places her hand inside his mouth, and they stay in that embrace for several minutes, the giant baby sucking on her hand like a pacifier.

In Dallas, Debra lives in what is called a soft contemporary home. The interior is almost entirely neutral with white walls and tall windows that make sharp-angled shapes of light on concrete floor tiles. The starkness is broken with large pieces by local artists from just about every major gallery in the city.

Debra’s appearance is part of the composition. Her clothing, structured like origami, is slipped over the petite build of someone who did enough ballet as a child to wreck her feet. The 69-year-old keeps her thinning hair dyed brown and cropped to the nape of her neck; each morning she sets it in a cloud of hair spray, brushing it straight back into a tight helmet. Her nails are short but polished. She has no kids and no pets, save for the elderly Rhodesian Ridgeback she occasionally dog-sits. Debra’s appointments begin as early as 6:30 am, during which she meets with high-end designers, curators, and collectors to discuss framing treatments for their Andy Warhols and Cindy Shermans.

Debra wasn’t born to this. She was adopted at 2 weeks old from what was then called the Edna Gladney Home, a home for unwed mothers in Fort Worth. In fact, it was Edna Gladney herself who handed a newborn Debra to a Grand Prairie couple, a housewife and salesman for a meatpacking plant.

Though her family didn’t live in the best of neighborhoods, Debra never wanted for anything. When she took up ballet, her mom figured out a way to pay for classes. Her dad’s meatpacking job meant there was always food on the table. College, though, was not in the budget. So when Debra graduated high school early at the age of 16, she moved out and started working. She was so broke in those years that, to pass a vehicle inspection, she borrowed tires from a friend’s car and put them on her own clunker because she couldn’t afford to replace her threadbare set. When an older man came along and asked for her hand in marriage, it was a relief.

By the time that marriage dissolved, when Debra was in her early 30s, she could fry a damn-fine pork chop but had no skills or advanced education. She managed to keep her North Dallas home by renting out the second floor. A friend had framing equipment, and, seeing an opportunity for self-sufficiency, Debra asked how to use it.

She could sell. That was the secret to Debra’s early success. Connecting with people had always come naturally to her. Debra’s first big commission was to reframe art for the savings and loan buildings acquired by Gerald Ford in the 1990s. When skill caught up to salesmanship, Debra was slammed, working every day and into the night. She was so exhausted that she couldn’t see straight enough to sign checks for supplies. She finally hired an assistant and then brought in an apprentice who works with her to this day.

Throughout her life, Debra was a loyal daughter to the woman who raised her. When her mother developed dementia, Debra moved her into the best senior living home she could find, and not a day went by that she did not visit. Still, over the years, Debra couldn’t help but wonder, Where did I come from? She was a mystery to herself. When Debra finally took up golf in her 40s after being interested in the sport since childhood, she wondered, Did my birth mom play golf?

Golf turned out to be fated for another reason: it’s how Debra became close with Scott, a real estate attorney with his own law firm in Dallas and a bachelor pad near the former Four Seasons Resort and Club in Las Colinas. They were golf buddies until the day that Scott, a Harrison Ford look-alike with a dry sense of humor, called Debra to confess that he thought of her as more than that. He had been living such a monastic life since his own divorce that he didn’t even know the guest code to his condo. He eventually moved in with Debra in her North Dallas home, but she was wary of marriage. It hadn’t worked out the first time for either of them. Plus, she didn’t want her hard-earned success to be eclipsed by a husband.

Debra’s husband, real estate attorney Scott Jackson, has become an eager naturalist and keeps a pair of binos handy with which to identify the carmine bee-eaters and crimson-breasted shrikes.

Africa moved the needle. Debra had always been fascinated by the continent and dreamed of going on safari. But Scott was a lawyer, and lawyers take time off when they’re dead. Debra made a proposal: surely Scott’s clients would understand two weeks off for a honeymoon. They married at the Lovers Lane United Methodist Church in 2000, the minister their only guest, and hopped on a plane to South Africa shortly thereafter.

The first wild elephant the couple laid eyes on was sleeping. Debra was transfixed. The other tourists were practically yawning with boredom, but she pleaded with the guide not to drive away. She was in awe of the giant creature that has walked our planet for 60 million years.

Their second visit was memorable for a different reason. This time their destination was Botswana, a landlocked country just north of South Africa that is home to the largest elephant population in the world—130,000 in a country the size of Texas. While out on an afternoon game drive, a guide stopped to host a picnic in the bush. A tracker walked to the far side of a termite mound for a cigarette and never returned. The group got back in the truck to look for him, and they came across a gruesome scene. A lion had taken and killed the lone tracker.

The safari company brought in a counselor to talk to the stricken guests and grieving staff before temporarily shutting down the camp. As Debra and Scott were leaving, the counselor stopped them. “I hope this doesn’t ruin Africa for you,” she said. “You have to understand that this is how we live. There is not a person in this country that does not know someone who was killed by an animal.”

Debra and Scott left feeling shell-shocked. They wanted to grab strangers by the shirt collars and tell them what they had seen. It was after their Dallas return, while sitting in traffic on I-635 behind a fatal car crash, that they had an epiphany. This is the danger Americans take for granted. The danger in Botswana was nature. “You know, people forget this isn’t Disney World,” Debra says. “This is the wild, wild west. But that’s what I love about it. It’s untouched.”

The untouched land and the elephants it sustains would call Debra back again and again for more than a decade. For years, all Debra and Scott hoped for was to witness an elephant playing in the water; they couldn’t imagine actually touching one. In 2012, Abu Camp gave them that opportunity. The Botswana safari lodge, then owned by Microsoft founder Paul Allen, was unique in that it allowed guests to walk with a semi-wild herd every day.

The first elephant Debra ever touched was a gentle pregnant female named Kiti. Debra asked Scott to return with her the following year so she could see the baby, but she was shocked to learn when they arrived that Kiti had died six weeks after giving birth. The calf, named Naledi, meaning “star,” had gotten dangerously close to death herself without her mother’s milk.

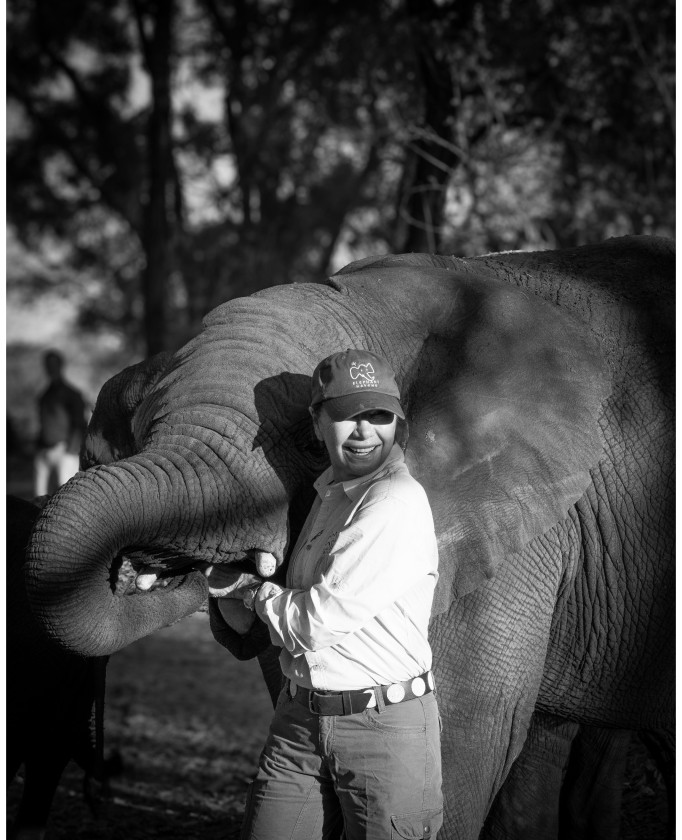

The elephant handlers were keeping Naledi in isolation to try to get her to drink from a bottle when Debra first met her. The quarantine gave Debra an unusual amount of time with the baby, and she stayed as long as the handlers would allow. She got to know the handlers as well, including Bee, Onks, and another named Akanyang “AK” Mosabata. Onks was Naledi’s caretaker one day when he said something that changed everything for Debra. “You know, if you keep coming back, she will remember you,” Onks said. That was it for Debra. From 2013 to 2018, she flew halfway around the world every few months to see Naledi, and she never missed the elephant’s birthday. Every year, she and AK used a springform pan to make a cake out of livestock pellets. “That’s when I realized you could have a really good friend as an elephant,” Debra says.

She last saw Naledi in 2018, several months before the elephant was released into the wild. “I know today if I went out to see her, she would still come running,” Debra says. “I know she wouldn’t forget.”

Names are not taken lightly in Botswana. Like a thoughtful tattoo, they carry meaning attached to an event, a feeling, a hope. Onks’ full name, Onkobetse, means “obey.” Boago means “foundation” or “building.” Akanyang means “think.” If a woman has a miscarriage, it is said that the baby was too perfect, so the mother might name her next child Broken so God will not take it.

After several days in Elephant Havens’ care, the new rescue gets her name: Neo, meaning “gift.” Over the days, Neo becomes calm enough that the handlers start doing “drive-bys,” walking the herd past her boma, the curious calves sticking their wiggly little trunks between the posts to sniff and feel the new elephant’s face and ears. As Neo starts to fill out, the dehydrated grooves at her temples become less pronounced, and she begins allowing handlers inside her boma.

One morning, we follow the rest of the herd while the elephants freely forage around the 140-acre grounds. A debate over names breaks out between two handlers, Eric and AK. All the handlers had already cast their votes for two other recent rescues currently called Big Boy and Little Boy. It was decided that Little Boy would be named Makoba, meaning “knob thorn,” since he was found on the banks of the Makoba Lagoon. (It was also apropos because he has a stumpy, injured tail, likely swiped by a leopard.) The votes, however, were evenly split over Big Boy’s moniker.

The Elephant Havens team choreographed a scene depicting the vet treating a new rescue.

Eric, an aspiring photographer who looks a decade younger than his 27 years, argues the case for Tshepo, meaning “trust,” while AK, a talented musician whose face is 90 percent smile, votes for Tsala, meaning “friend.” Eric’s case construction: for a few months during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Elephant Havens cared for three baby rhinoceroses in a large enclosure as a favor to the government, which didn’t have the staff available to guard the highly poached animals. One of these orphaned rhinos arrived all alone, so Bee gave the little guy a sheep to keep him company and model the art of grazing. They called the sheep Tsala, because he was acting as a friend. And this, Eric emphatically argues, is why they absolutely cannot name an elephant Tsala. Because Tsala is a sheep’s name.

AK’s refutation is based on the basic notion of phonics. Tshepo sounds too much like Tshepi, the name of the herd’s current matriarch. And what were they going to do when they call Tshepo and instead Tshepi answers?

“An elephant is your friend,” AK says. “For a long time these babies have been your friend.”

“For a long time these babies give us their trust,” Eric says.

“For you to trust someone is to become their friend,” AK says.

In the end, AK wins and Eric loses. Big Boy gets the sheep’s name.

Many a human through history has tried to raise baby elephants, but they are such fragile creatures, their stomachs especially. Like human infants, a young elephant’s digestive system can’t break down the proteins in cow milk. The solve was giving elephants infant formula, the same stuff our human babies take. The first person to successfully feed and raise orphaned elephant calves was Daphne Sheldrick in Kenya. Sheldrick was inspired to write the story of her life, Love, Life, and Elephants, after the elephant she thought was her rewilded Eleanor grabbed her with its trunk and threw her “like a piece of weightless flotsam,” smashing her body on boulders and shattering her leg. The wild elephant was not her Eleanor.

The calves at Elephant Havens drain 2-liter bottles of infant formula every three hours, around the clock. Bee recently donated 10 goats to 10 farmers, with the goal that the farmers will breed and milk the goats. Bee will then buy the goat milk for his elephants at a price significantly less than commercial infant formula. His elephants will get natural, nutritious milk that agrees with their nascent bellies. And the farmers will make an income. Win, win, win.

Debra says repeatedly that she and Scott are not necessary to the Elephant Havens operation. Bee runs the ship. Bee knows how to raise baby elephants. Bee suited up and knocked on government doors in the capital city of Gaborone for a full year before the government finally granted the sanctuary’s approval. But Bee says that when he decided Botswana needed an elephant orphanage because no protocol or care facility existed, he knew Debra and Scott were passionate enough about Naledi that they might help.

“That’s great!” Debra said after Bee laid out his plan. Bee’s eyes went wide. “You don’t understand,” he told her. “I can’t do this without you.”

Debra left that meeting in a daze. She was a kid from Grand Prairie, an art framer in Dallas. What did she know about starting an elephant orphanage in Botswana? Her husband, on the other hand, did not flinch. Scott happens to have the unflappable disposition of someone who wears flip-flops in thornbush country, as well as plenty of experience with property developments and business plans. And he, too, loves Africa. Though Scott’s love of the continent, I suspect, springs largely from his wife’s gushing main stem. Africa has a hold on Debra’s heart, and Debra has a hold on Scott’s.

Most importantly, Scott had the faith in his wife to say to her, “Debbie, if anyone can make this happen, it’s you.” And so she did.

When Debra sent an email blast to start fundraising, she got a call from her former assistant, the first employee she ever hired. After 10 years with Debra, the assistant had left to help run her husband’s company. The couple asked to get together for dinner to hear Debra’s pitch. Debra thought she might collect a hundred bucks. Instead, the couple, which had just sold their company, wrote a check for $250,000. With matching funds from Debra and Scott, Bee now had enough money to get an elephant orphanage off the ground.

Some years later, when Debra sent out another call seeking funds to cover a mini-bus to shuttle Batswana schoolchildren, many of whom walked several miles to school at the risk of getting trampled by elephants, that couple bought not one but two buses out of concern that the first bus might break down and leave kids in a lurch. Yet the couple has never once visited Elephant Havens. “They just believe in me,” Debra says.

Because of Debra’s connections, you can find Dallas all over this small patch of Botswana earth. The Dallas Zoo set up the sanctuary’s lab, which checks for common elephant diseases. It also helped pay for a bridge, which allows locals to walk or drive to town during floods, and an electric fence that surrounds the 1,000-acre transitional property for older elephants, called the “soft release.” (A 12-year-old Dallas girl convinced her parents to donate the initial $50,000 needed for the fence.) Dallas folks have funded community wells, school computer labs, and the cleaning of hazardous bat guano from the ceiling tiles of the elementary school. When families in the community lost their tourism jobs during the pandemic, Dallas-based chef Kent Rathbun and his wife, Tracy, made sure they were fed.

The community around Elephant Havens was skeptical when the sanctuary opened in 2018. Some were downright furious about an orphanage saving the crop-raiding beasts. But after all of the local efforts, and Bee’s ongoing work to invite local Batswana to meet the herd and to educate them on best practices with elephants, the community has come around. The 1,000 acres Elephant Havens now uses for the soft release was donated by the local tribe. The elementary school has placed a plaque bearing the name of an Elephant Havens rescue on each cinder block classroom.

Despite the improvements, it’s still not, as Debra says, Disney World. One Elephant Havens staffer went to a public hospital with a headache; his paperwork later said he died of a migraine. That man’s twins, Benny and Benson, tall young men whose faces have not yet lost their youthful roundness, both work at Elephant Havens. Their mother also recently died. Elephant Havens now contracts with a private physician for staff care, and Debra and Scott have personally paid for numerous funerals.

There is always a need, and always more money to raise. Debra and Scott, who pay for their own travel, try to visit every other month, maxing out their 90 allowable days every year. Debra lives in constant fear of making a misstep with the government, doing something that will shut them down, sending her baby elephants to die in the wild and the staff into poverty. She’s had a case of shingles since Elephant Havens opened, which has never gone away long enough for her to get inoculated. Debra has so much to lose now, because she has so much to love.

Debra wants to take me to the soft release before I leave. She broaches this sensitive subject with Onks over breakfast. Onks has a stocky build, a sonorous voice, and bright, emotional eyes. When Debra asks him to take us to see the older elephants, he stares back at her like his eyeballs are going to crack open. “It’s not dangerous,” Debra says to me. “We’re just not supposed to do it.”

In January 2022, the handlers, Debra, and Scott walked a foursome of their 5-year-old elephants 6 miles north to their new home: the 1,000 fenced acres of pure Botswana land all to themselves. Well, themselves and various antelope—impala, kudu, and duiker—all predators having been driven out or darted and removed. When this elephant parade reached its destination, two important things happened. One, they met three young elephants brought in from another sanctuary, which meant a social order had to be established. Even without mature elephants to model the behavior, orphaned calves still naturally form adopted family units led by a matriarch. In this case, the leader was established in quick, dramatic fashion. The foreign matriarch picked a fight with one of the babies of Elephant Havens’ matriarch, MmaMotse. MmaMotse then charged the offending elephant, ramming her wide flank and laying her out flat in the dirt. All was well after that.

The other important change at the soft release: the elephants lost their names. They were no longer MmaMotse or Lerumo or Debra’s babies or Onks’ babies. Entering the soft release marked the start of their transition to the wild. After five years in the fenced acreage, the matriarch will be collared with a tracking device and released with her adopted family. The collar will be removed after 10 years, making the whole raising and rewilding process about 20 years. Only God knows if Debra will be around the day the first herd is officially free.

Debra climbs into the bed of a truck and smacks the roof to let Onks know that she’s ready to go. She stands, holding on to a rail, bouncing as Onks speeds over sandy roads, her shirt billowing and slapping in the wind. Inside the cab, I’m gripping the grab handle as Onks talks about working with elephants. “The most important thing is love,” Onks says. “If you give them your heart, they also give you theirs.”

And then he makes an admission: his hesitancy to visit the big elephants isn’t just in deference to company policy. “It’s hard to me,” he says. “When I see them, I get sad.” These were babies he bottle-fed every three hours for several years. The fact is, Onks spent more time with these calves than his own human children. He cries almost every time he sees the herd out there living their own lives. When we pull into the soft release, I ask Debra if seeing the big elephants makes her sad. “No,” she says, puffing out her chest. “It makes me happy.”

Onks and Debra on the lookout for elephants with no names in the soft release.

We get out of the truck and cut across the acreage at a fast clip. I keep my eyes trained on the rough terrain. We hop over animal burrows and weave between small trees and dried bushes, nothing left on them but gnarly thorns. Debra speaks loudly and whistles along the way, hoping the elephants will hear. After 25 minutes, we hit the far side of the fence and take a right, walking along the fenceline until we get back to the truck. Onks drives us around the perimeter for one last shot at finding elephants, but the only signs of life are a few men repairing a section of the electric fence.

On the way back to the main camp, Debra and I trade places. She gets in the cab, and I stand in the back. I realize then that this—riding in an open truck bed with Onks’ lead foot on the gas—is the way to take in Africa in all its glory. I cinch the strap of my hat until it digs into my chin. My boots catch air as we hit bumps, and I drop into a crouch to avoid tree branches. I learn to anticipate turns and adjust my stance like a surfer’s. When the tires lose traction and slide in the sand, I feel as if I could soar like a fish eagle through the blue Botswana sky.

Suddenly, the truck comes to a stop in the middle of the road. Debra gets out, spins her back to a thicket of bushes, and pulls her pants down while lowering into a squat. Her eyes catch mine before I realize what she’s doing. Her arms are crossed over her knees, and she gives a little shrug while stating the obvious: “I don’t even bother going behind a bush.”

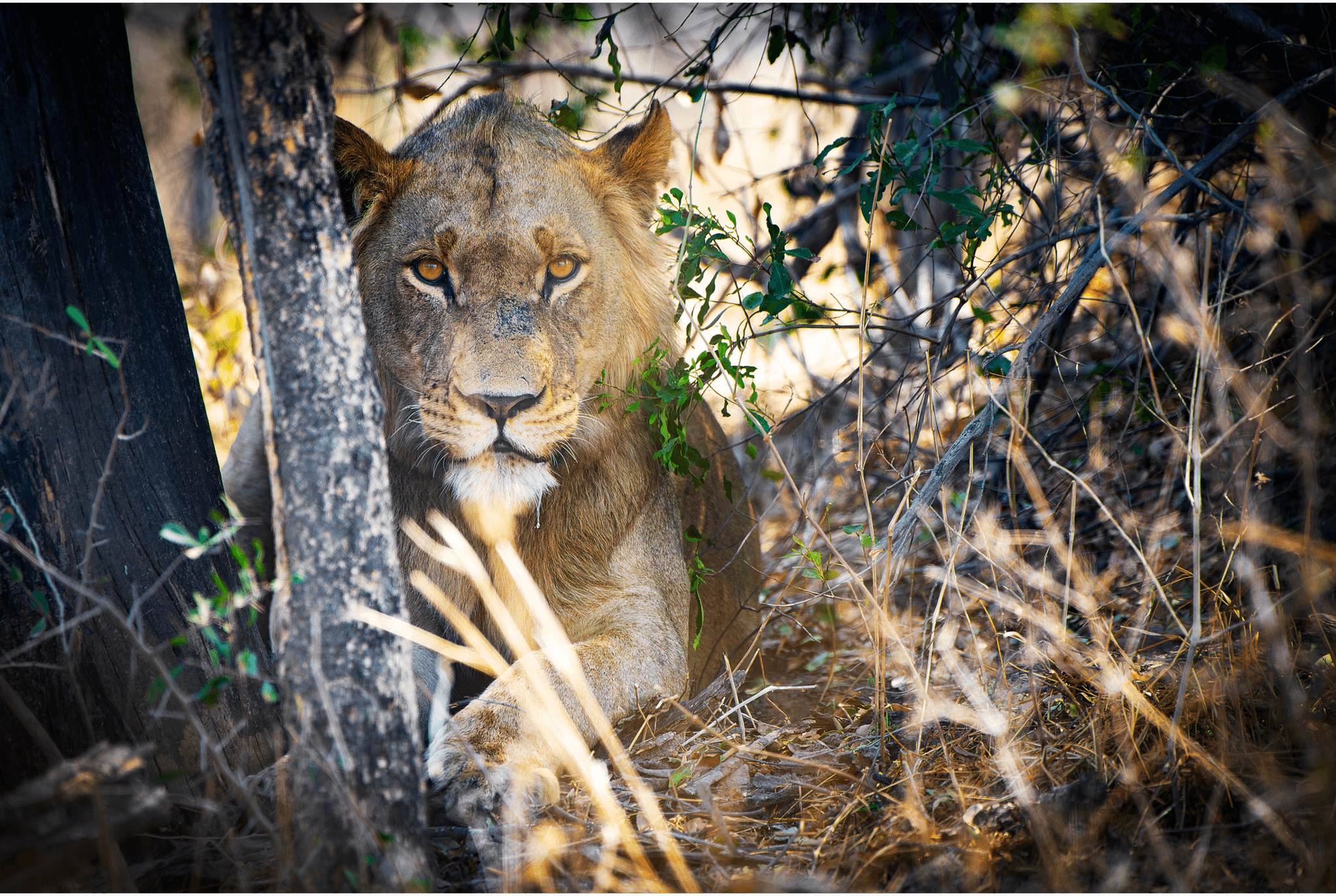

A few days later, we have another opportunity to return to the soft release. This time, we’re there to see about a lion. The day after our first hike, the fence repairmen discovered a lion pride that had gotten separated while the electric fence had been turned off. Now that it was back on, at least one of the predators was still stuck inside.

On a blistering Saturday evening, we go looking for the lion. As Bee turns the truck onto the sandy path we had walked days before, we find deep, defined paw prints. Fresh ones. “How long ago?” I ask. “Five minutes,” Onks says. I’m standing in the truck bed with Scott and Onks, and the breeze graciously dries my sweat-dampened clothes as we drive on. A few minutes later, the truck stops again. “Elephants,” someone calls out. I squint, and in the distance I can see elephant shadows against the violet horizon. Debra hops out of the cab and climbs into the bed. Her face has gone stony, and she fumbles with the focus rings on a pair of binoculars.

The final lion remaining in the soft release was sighted before being safely removed.

“I don’t know why this means so much to me,” she says under her breath. I borrow another pair of binos and catch sight of an elephant as it disappears into a thick grove of silver terminalia trees. I pull the binos down to look for movement. They’re gone. We will finally find our lion the following morning, a young male panting in the shade of a magic guarri tree, but this remains our only glimpse of Debra’s former babies.

Onks opens a cooler and starts passing out cans of soft drinks and a Botswana lager that is, oddly, called St. Louis. I take a sip of icy beer and look back. Debra is leaning over the rails of the truck bed, binos up, still searching for the elephants who have no names.

Before I went to Africa, Debra told me a story.

On the morning of March 26, 2017, she woke up and walked into her living room, still groggy and wearing pajamas, having returned in the middle of the night from a trip to see Naledi. Her longtime bookkeeper had let herself in as usual, and they exchanged pleasantries. Then the bookkeeper made a startling announcement: “I found your family.”

“What?!” Debra had no idea what she was talking about.

Months earlier, the bookkeeper had asked her to spit in a vial. “I just want to know your nationality,” she told Debra. The Ancestry.com results were no surprise. Scottish and Irish descent, just as the adoption agency had told her parents. But without Debra’s knowledge, the bookkeeper left the account open and eventually came into contact with a man identified by DNA results as Debra’s cousin.

Debra immediately dialed the number of this supposed relative. She knew only a little about her birth mother. In her 30s, Debra asked the adoption agency for any information they could provide. She found out that her parents had been teachers. She knew her mother was a middle child who had a younger brother and an older sister who was married and pregnant at the same time she was. Debra knew her mom had brown hair and brown eyes just like her.

As she compared notes over the phone with a man named Clark, the details all aligned with that of his aunt Rosalind. Clark’s mom was the oldest of three, and his birthday was only a month before Debra’s. Rosalind had died a decade earlier, but she had two sons, Steve and David Platcow, who had no idea their mother had birthed any other children.

Debra Stevens captured with her namesake, Debra Motamma, Onks’ youngest child.

“I’m not looking for a family,” Debra told Clark. “If you think that my brothers would not think less of their mother, then by all means tell them. But if you think they’ll think less of her, don’t. I’m not going anywhere. This is your decision.” Debra had lived more than 60 years not knowing anyone who shared her blood. Her whole life, she had cooked up delicious fantasies about who her mother might be, and she was afraid of learning the reality. She especially didn’t want to turn anyone else’s lives upside down.

The next morning, Debra sat down at her desk to catch up on work that had piled up since she had been away. When she opened her inbox, she found three emails from people she had never met. The subject lines read:

Thank God Another Girl!

Welcome to the family

My Beloved Sister

Hours before Debra received those emails, 900 miles away in a suburb of Chicago, Steve Platcow was watching Lawrence of Arabia with his family when the phone rang. His cousin was talking in circles. Something about a gene test and a first cousin. “Spit it out, Clark,” Steve said.

Steve had been especially close to his mother, but he had always felt there were some holes in his understanding of her life. He was particularly curious about her adult life before kids. When he probed, she spoke vaguely of being a teacher and taking summer classes in Mexico. Quietly he wondered, Why did she wait so long to marry? She was practically a spinster by 1960s standards. As soon as Steve’s cousin shared his conversation with an adopted woman in Dallas, those snippets of odd conversations came into focus, and Steve saw a clear picture of his mother for the first time in his life.

The phone call from Clark had come just a few months before the 10th anniversary of Rosalind Platcow’s death. Though she lived until 77, her death had been a shock. One moment she was reading; the next she suffered a profound stroke. The family had buried Rosalind’s own mother, age 101, only a decade earlier. There were centurions on both sides of Steve’s family. He was raised by spry 80- and 90-year-olds. He felt robbed.

Rosalind had been a public servant her entire life, working as an elementary school teacher until middle age, when she finally followed her dream of becoming a nurse. She went back to school and took a job at a low-income hospital. Though Rosalind never told her sons her full story, Steve believes she raised them in such a way that they would someday be able to accept her full truth.

“There was a pragmatism that she prepared us for in regards to all of the possibilities that life can bring,” Steve tells me over the phone. “For her, it was about the opportunity to make the world a better place—spreading love and accepting goodness wherever you can find it. So there wasn’t any aspect of this that wasn’t recognized as a gift from her as well as from God. We are at the 10th anniversary of my mother’s passing, who we miss dearly, as we find a literal piece of her. It was the greatest thing that could have ever happened at that moment.”

A time of sorrow turned into celebration. Debra and Scott flew to Chicago a few weeks later to meet Debra’s biological relatives for the first time. The family presented her with heirlooms and shared their favorite family stories. They held an open house, inviting friends and extended family to meet the new sister, with instructions to regale Debra with memories of her mother.

Many of them told Debra how much she looked like Rosalind. “She’s the spitting image of my mother, but she has my grandmother’s eyes,” Steve says. “It’s unbelievable, uncanny, like seeing someone back from the dead. It’s so obvious she’s one of us—in temperament, in humor—and it’s not just how she presents physically but spiritually.”

As Debra connected with her family, they made some bizarre discoveries. Steve and David grew up in a small subdivision of Indianapolis, Avalon Hills, the same neighborhood in which Scott was raised. Scott is almost a decade older than Steve, so the men didn’t cross paths in school or extracurriculars, but as they compared notes, they realized they shared a second-grade teacher and learned how to golf on the same course.

Yet the biggest revelation began with photos of Debra and a little elephant. Steve had seen her Facebook profile. “What’s this with Africa?” he asked. Debra told him about Naledi and her friends on the other side of the world. “You’re not going to believe this,” Steve said, “but your mother spent the first eight years of her life in the Congo.”

Steve told Debra that their grandparents had been missionaries in the Belgian Congo of Africa, where they taught Congolese residents how to farm and irrigate and convinced the tribal chief to let them educate the girls as well as the boys. They formed schools that are still in existence today. But some of Rosalind’s most significant memories from Africa—the most painful ones—were watching her family try, and ultimately fail, to save orphaned elephants.

A year after their introduction, Debra called Steve with good news. She was starting an elephant orphanage in Botswana. In a blink, Steve, an ad man by trade, had the perfect name for the venture: their mother’s maiden name was Havens.

On Neo’s seventh day at Elephant Havens, Debra and AK go into her boma to give her a sand shower and make a mud wallow in the corner. After a while, Debra asks AK to check with another staffer on some land she heard was for sale. AK stands outside the boma, speaking on the phone rapidly in Setswana, the only discernable word being “mother.” When he says it, Debra whips her head back. “Did you just call me mother?” she asks, beaming.

It doesn’t surprise me. I had seen pictures of Bee’s wedding. Debra was wearing a ceremonial dress that Bee’s aunties had made for her the day she and Scott flew in. With his mom’s permission, Bee asked Debra to perform the mother’s role, handing over the dowry to his bride’s uncles. When I told Bee that I saw his wedding pictures, he gave me one of his hard-won smiles and nodded, saying, “It was pretty special to have two mothers.”

The young herd has free range over the 140-acre sanctuary during the day. The elephant calves graze, rough house, and romp around in the mud wallows at their leisure.

There was also the afternoon that Bee brought his two boys and Onks’ two youngest to camp. (Bee’s wife, many months pregnant, was happy for the downtime, having spent the previous day on her feet, slaughtering more than 100 chickens to sell.) That day, I watched Debra pull Onks’ 5-year-old into her lap, wrapping her arms around her namesake. Little Debra, they call the child.

After saying good night one evening, I was searching the main area for my hat. Out of the corner of my eye I saw Debra hook her right arm around Onks’ neck and touch her right temple to his left.

“I love you,” she said.

“I love you more, more, more, more, more,” Onks said, shaking his head slightly with each word.

“I love you most,” Debra said.

Onks lifted his chin, looked Debra in the face, and gave one definitive nod.

“I love you more than most.”

While AK continues his phone call, Debra tells me a story. Back in her 20s, she visited a popular University Park psychic named Fan Benno. When Benno held a person’s hand, she claimed to see inside them—their past, present, and future. On that visit, Benno told Debra that her birth parents had been teachers. Benno also said something that puzzled Debra for decades. She said Debra would have a whole bunch of boys but would not give birth.

When AK gets off the phone, he and Debra go inside Neo’s boma and make a dirt mound, and then they both get on the ground and lie down. Neo circles them and then kneels low, rolling onto her side next to AK. And for just a minute, the elephant forgets to be afraid.

Several months after my visit to Elephant Havens, I catch up with Debra in her Dallas office. She is back in her origami clothes, her hair set in its helmet, and her nails are polished in pale pink. She and her colleague have just finished the complicated and nerve-wracking framing of a 12-foot Warhol. She has gone back to Botswana twice since my trip, and she has lots to share.

Within two months of my visit, Elephant Havens nearly doubled its herd. Botswana’s November rains never came, causing an uptick in conflict with humans and a messy situation involving a man-made pump pond. For days, handlers camped at the site, pulling babies free from the mud and back into the care of their mothers, until Bee managed to get his hands on a backhoe. Not surprisingly, Debra’s shingles are back.

In the middle of all the elephant chaos, Bee’s own human baby was born prematurely, weighing just over 4 pounds. Though she had a scary start, the baby girl is thriving and grows healthier every day. A name for this baby required no debate. Bee and his wife agreed on Haven.